Sex sells. There are a sort of always-online, or if you like millennial, Americanisms in force, as in the TikTok ad on YouTube I just got served where a narrating man walking in a forest pans his smartphone camera over the view, and a be-legginged woman walks through the shot, and he says of the (euphemistic) Nature that “Oh yes, it has the juice.” I presume that refers to a juicy behind, and all this to sell a social media platform.

One manifestation of the “sex sells” truth, interesting on account of its continuation of the trend of brazenly false advertising of free-to-play games and its construction of a distinctly 2020s symbology of the sexual relationship from the point of view of beleaguered men, is the ad campaign of Hero Wars. Awareness of the campaign is a fait accompli, as evidenced by certain up-in-arms Reddit threads; and yet the symbology deserves renewed attention.

Not least because the ad campaign, as managed by Nexters, subsidiary of Hero Wars owner and NASDAQ entity GDEV, shows no signs of letting up and broke its live action cherry in January. Brief commentary on that will serve as a segue into analysis of the commoner fare, i.e. ads consisting of 2D digital artwork.

The live action campaign, crafted by Zorka.Agency and run in Germany and Poland, sees a young man in a smoking jacket reclining in a chair and playing the mobile version of the game (if you’re unfamiliar with Hero Wars, its content will be clarified shortly). Looking at the viewer, the man opines that “Life can be a real whirlwind of stress,” and then his chair lifts him out of the window and into the eye of an actual storm. He has “one secret,” he says, that helps him “weather the storm anytime, anywhere.” He taps on his game, the storm clears up, and he’s landed in the palm of the hand of a giant, golden-tressed woman, who looks at pint-sized him with feminine affection. “Feeling like a true hero who deserves the best,” is how our protagonist sums up this happy situation. But the woman, who’s subject in the ad to a digitizing effect that implies she’s encounterable in-game (and whose presence taps into what Ads of the World calls with equanimity “the recent ‘Giantess’ trend”)—this woman is nowhere to be found in-game.

What’s to be found in Hero Wars? To take the browser version called Dominion Era as an example, the game is an “idle RPG”—one doesn’t really do much when it comes to the action except watch her party members battle against enemy waves and, once the metre is filled, click to activate a special ability. Outside of the combat, one buys and swaps out party members, equips them with items, and spends special gems and coins to level them up. Occasionally there’s a puzzle mini-game. The usual ads, which are the focus of this investigation, imply that Hero Wars’ contents are rather different.

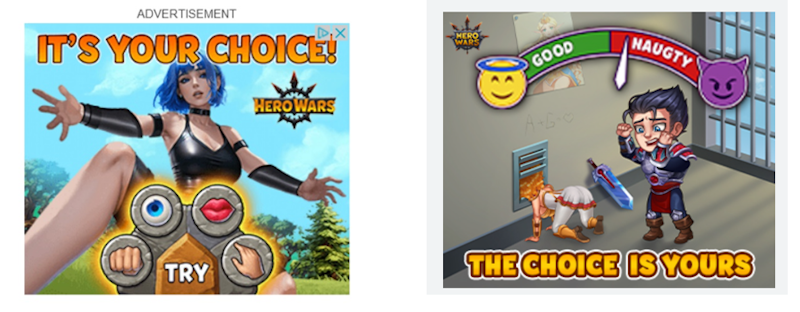

Exhibits 1 and 2. A pair of static ads.

Let’s begin with this pair of ads, to be found as mid-page units throughout the ‘net and also in the top-right corner of desktop YouTube. In Exhibit 1, a woman’s crotch is covered with the rather tragic fig leaf of a stone-wrought options-dial: one may fist, ogle, kiss, or finger. “It’s your choice!” She manages to appear supine and ready for ravishment even while upright, one knee on the grass and one foot out, and arms akimbo in invitation, among pastoral secrecy. In Exhibit 2, in a dinky pastiche of the “stuck in the tumble dryer” trope, a woman is on all fours, with her titillatingly draperied rear end on show. The rainbow-shaped gauge is bookended by halo emoji and purple devil emoji, and is split into two halves: good and naugty [sic]. That “The choice is yours” is once again emphasized, and the dial appears to be tending to naugty.

These two ads, which represent the tip of the iceberg of questionability, are part of a huge suite of ads run by GDEV. In a press release in late November, the company shared key stats about its performance during the first nine months of 2023. “Selling and marketing expenses” had increased by $60 million year on year, amounting to $172 million in total from January to September. That increase in spend could, in the main, “be attributed to considerably more investments into new players in the first nine months of 2023.” The flood of Hero Wars ads has been proverbial on certain subreddits, and GDEV doesn’t discriminate: even though personalized ads are turned off for me in the Google Ads Center, I still get Hero Wars pre-roll ads on YouTube regularly. In the Ads Transparency Center page for Nexters (GDEV’s subsidiary), when sorting by location = “Anywhere,” the international scope of the ads is plain to see. “Spiel mit uns!”, declares one; another avers that “Este jogo é um tesouro para fãs de RPG.” New ad variations are added every day… and they can be eyebrow-raising.

Exhibit 3. White knight and moo-moo mother.

In this video ad, the Hero Wars mascot Galahad finds himself in dire straits as but a human plough-horse upon the field. His captor, half-cow, half-human woman, brands him on the buttock with what looks like our old friend the purple devil emoji—rather a “naugty” [sic] act. Suddenly set upon by wolves, the cow lady is compromised—and Galahad steps up to become white knight, fending the beasts off with his axe. The cow lady and her new hero Galahad elope to her encampment, where she carries him around like a baby, and spots him for sit-ups. Needless to say, the episode of the bovine damsel does not occur in-game.

Like other mobile-game companies, GDEV gets away with advertisements whose content is never or rarely found in-game. One likely reason, alluded to earlier, is that the games are free to play, so that the false advertising doesn’t involve a monetary swindle. There are interventions nevertheless, as when the United Kingdom’s Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) slapped the wrist of Playrix, producer of the serene-sounding Homescapes and Gardenscapes games. The games belong to the so-called “match-three” genre, in which objects, stacked in a grid subject to gravity, are shuffled and matched with corresponding objects so that they disappear, leaving room for more objects to fall down. (The most famous match-three game is Candy Crush. Though an unjustified fancy, one likes to think they’re nieces and nephews of Bubble Bobble and its ilk, and that it’s all basically descended from great-grandad Tetris.) In the ads, though, Playrix had put footage of puzzles not apparently in the game: puzzles in which pins and poles are yanked out in sequence to avert dangers and access goodies. This is a class of misleading advertising content, i.e. the “How to Loot” genre—reskinned variants are found in Hero Wars ads too.

The sexual edge to Hero Wars ads distinguishes them from Playrix’s work, and it’s to this edge that we must return—though as Tousif, founder and editor-in-chief of GamingonPhone, reminded me, “It is not only about Nexters’ Hero Wars.” “This quick gain tactic of putting sexuality in front is very harmful in the long run,” said Tousif. He added that, on the business side of things, the tactic “may impact [a] company’s PR potential,” leading to a situation where “no investors, or employees would be interested to associate with a brand like this.”

As in any ad campaign worth its salt, GDEV probably tests variant ads and pushes, and refines, the ones that generate returns. While an ad could conceivably boil down to a lowest-common-denominator message, pummelled through A/B testing into something like neutrality, the Hero Wars ads retain a kind of original artistic licence (or could a machine-learning tool dream up the premises we bear witness to in this article?). One presumes an interesting three-way junction, between original artistic licence (brainchild), actual pertinence to the viewer (or the viewer’s sexual curiosity), and optimization.

One of the most prevalent symbols in Hero Wars ads is the production line. In particular, this is the production line or conveyor belt of feeble men being fed to a woman who’s physically larger than them—a largeness that denotes her higher social standing, her being “out of their league.” That old black pill bitterness, then, whereby a disaffected Internet male decides that he’s ugly and women are materialistic succubae who want only to play with men’s hearts and get with chads, is refracted here through the symbol of the gamified production line. (Gamified: even watching these ads, there’s a reliable dopamine hit every time one of these beta males jumps into the cavern, or the basket, or whatever black receptacle the woman has prepared to harvest her pathetic suitors.)

Exhibit 4. The production line.

In this variation, awoogah-eyed simps shuffle towards an over-tall maiden. They try to pull the sword from the stone, to impress her, and because they fail, they’re chomped up by a green monster that comes out of her mouth. When it’s Galahad’s turn, he succeeds, but the maiden still eats him, then excretes him out of her lower half—a one-eyed, claw-mouthed being.

Each simp’s falling short of a standard of masculinity is met with a monstrous gesture of rejection. Galahad succeeds, but is rejected anyway—a defeatist narrative. The maiden’s monstrous bottom half, concealed beneath her wide dress and by the ground, suggests a distinction between pretty outside and ugly inside. Galahad is chased by the extending bottom half through the tunnel, and falls down into the desert, where a rival man steals the sword and, with his female companion, spits at Galahad before they run off.

Other ads reskin the same production line motif—in one variation, the men, socket-eyed oldsters instead of young simps, jump in turn into a man-shaped stone void, in a black-piller’s Takeshi’s Castle episode. (In this variation, Galahad is spat out the stone rear-end and laughed at by two level 99 chads.) In another variation, a giant woman spreads her legs and receives the production-line men into the space between them, leaving little to the imagination.

How is it that the ads have come to this? As noted by Neil Long in his article for Eurogamer, sexual ads about games go back at least as far as “those saucy ‘save me, my lord’ Evony banner ads from the late 2000s.” Sex sells, of course, and these ads represent a modern take on the sex sell which exploits feelings of being consumed and spat out by women, and ridiculed by men, in a competitive sexual arena where the odds are stacked against the (literal) little man. Riffing on the Evony injunction to “save me, my lord,” the message of the women in the production line ads could be said to have evolved into “I’ll punish you for trying to impress me, vassal.” There may be something like self-deprecation, or the hope of revenge, motivating players to click here. (It must be noted that the first ad example, that of the woman with an options dial for fig leaf, does forecast a sunnier time for the player.) The ads may also be the expression of some sexual quirks on the part of the animating department at Nexter’s, apart from the audience-focused question of what will sell. When one sees such things as vore and pregnant women in videos (collected here), one wonders if some of this is kinks finding a creative outlet.

It’s clear that the legal freedom to produce ads with no relation to the game itself means that Hero Wars ads will be able to proliferate, not just in terms of re-skinnings of the same content, but also introduction of new content—and content that connects back to other content. An example of this connecting-back is a recent ad in which Galahad spends time with a nice butterfly woman, until she sadly transforms into a pupae or grub. A goblin arrives on scene, steals the grub away, and baits his fishing rod with it before casting. Galahad stabs him in the back, and we realize at this point that we’ve seen this part before. The backstabbing of the fishing goblin was in another ad, but we hadn’t seen the backstory then: how the goblin acquired his bait. The ads are filling in gaps and stitching distinct episodes together. We therefore have a situation where an expanded universe of Hero Wars is being created within the advertisements. How much further down we go remains to be seen.